Managing the Chaos of New Product Development

A Mayo Clinic engineer describes hard lessons learned from years of new product development.

Developing a new medical device is inherently risky. When defining a new device, I’m not referring to an enhancement or the next generation of the same product, re-designed simply to extend the patent for a few more years without significant improvements. I’m describing innovative products that add capabilities that don’t exist or combine existing capabilities in new and interesting ways.

To manage this risk, companies have adopted standardized practices in an attempt to bring order to what is an extraordinary chaotic process. The most common process is the infamous waterfall development methodology. Medical device manufacturers can mistakenly feel that a waterfall methodology is the preferred method after taking a cursory look at the FDA guidance documents. But unless your product is extremely well understood, this process will ensure that the device requires extensive rework, fails entirely, or that the product development team entirely ignores the methodology, other than for mandated reporting to management.

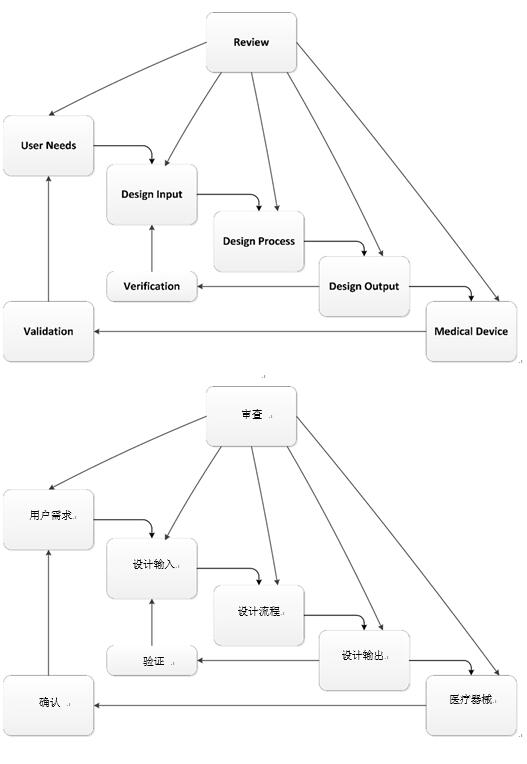

FDA Design Controls Guidance—Waterfall Methodology

When developing a new device, you often don’t know where you are going. You and your customers don’t always know what the end-product will be. You may have some idea of the problem to be solved, but if you are truly working on an innovative product, it is unlikely that the solution is obvious. This makes planning the product development cycle from end to end an exercise in futility, causing frustration to both managers and developers. I will argue that you can’t avoid moving between development and analysis when solving any non-trivial problem.

This is not to suggest that you ignore process. In fact, process is even more important because it is the only thing that can bring some semblance of order to new product development. The question being asked over and over then, is “what is the right process?” Unfortunately, the answer, as is often the case for important questions, is “it depends.”

What, then, is an organization to do? FDA—and good sense—mandate that a defined, repeatable process be used. The agency doesn’t, however, impose a particular methodology—despite its questionable inclusion of the waterfall methodology in its design controls guidance documentation. I will argue that an evolutionary or iterative development process is a superior and more realistic design methodology. This type of process allows the development of a gradual understanding of both the problem and the solution. This is especially important when the solution isn’t known at the beginning. An evolutionary development process is well suited for the development of both incremental or transformational products. However, the challenge of choosing the right process remains. A slight reinterpretation of the archetypical medical device process drawing can show how easily an evolutionary design process can be achieved.

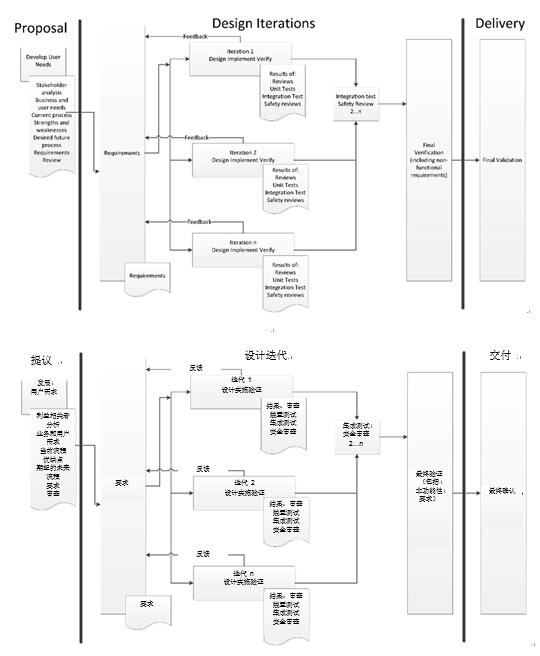

Evolutionary or Iterative Design Process

By focusing on the constant evolution of these key design deliverables, at the end of the product development cycle, we not only have a revolutionary new product, we also have our completed design input and design output documentation—in accordance with our FDA 21 CFR 820–compliant quality management system.

Evolutionary design is not an excuse to avoid process or the burdens of regulation. It does, in fact, require more discipline to manage the ambiguity and relies on an unfailing trust in the process. To be successful leading a team through an iterative design process, one must have an understanding of the intent of the regulations, a clear idea of how to satisfy the intent through an iterative process, and an ability to deal with uncertainty. Managers and stakeholders can be doubtful until they see the steady drumbeat of progress. Their support grows as they begin to understand how an iteration or two that fails can allow for a quick change of plan and new approach without a major reworking of the schedule.