Implant Translates Brain Activity into Speech

Hundreds of microscopic sensors on an implantable polymer film the size of a postage stamp record brain activity, which is then decoded into words and sounds.

Back when Lucy was still visible in the sky with diamonds and the Beatles were shrouded in a purple haze, John Lennon reportedly wondered if it wouldn’t be possible to implant some sort of device that would turn his thoughts into audible song lyrics without involving his vocal cords. I’m guessing he would have been fascinated by research at Duke University, where a team of neuroscientists, neurosurgeons, and engineers are developing a brain-computer interface that translates brain activity into speech.

As described in a paper published this week in Nature Communications, the research may one day allow people unable to speak because of neurological or motor disorders to regain the ability to communicate.

Current technology that enables this sort of communication is very slow and cumbersome, according to Gregory Cogan, PhD, a professor of neurology at Duke University’s School of Medicine and one of the lead researchers in the project. The best speech decoding rate currently available clocks in at about 78 words per minute, whereas people speak at around 150 words per minute, according to an article in Duke Today. That lag, writes Dan Vahaba, director of communications at the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, “is partially due to the relatively few brain activity sensors that can be fused onto a paper-thin piece of material that lays atop the surface of the brain. Fewer sensors provide less decipherable information to decode.”

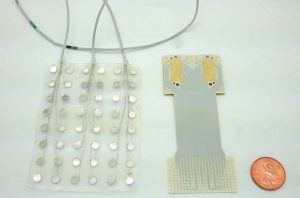

Cogan teamed up with fellow Duke Institute for Brain Sciences faculty member Jonathan Viventi, PhD, whose team packed 256 microscopic brain sensors onto a postage stamp–sized layer of medical-grade liquid crystal polymer thin film.

|

Image courtesy of Dan Vahaba/Duke University

|

| The device developed by Duke engineers (right) carries twice as many sensors in a smaller footprint than current speech prosthetics with 128 electrodes (left). |

With the assistance of neurosurgeons at Duke University Hospital, they recruited four patients undergoing brain surgery to test the implants. The patients, who were not receiving treatment for speech disorders, were asked to repeat a series of nonsense words and sounds, which the implant recorded. The researchers had a very narrow window in which they could operate — about 15 minutes per patient. Cogan compared the process to that of a NASCAR pit crew in the Duke Today article.

Biomedical engineering graduate student Suseendrakumar Duraivel then fed the neural and speech data into a machine-learning algorithm to see how accurately it could predict what sound was being made based solely on the brain activity recordings.

Results were mixed. In some cases, the decoder got it right as much as 84% of the time, but accuracy generally fell into the 40% range. “That may seem like a humble test score, but it was quite impressive given that similar brain-to-speech technical feats require hours or days worth of data while Duraivel’s speech-decoding algorithm was working with only 90 seconds of spoken data from a 15-minute test,” writes Vahaba.

Duraivel and his mentors are now working on a cordless version of the device thanks to a recent $2.4 million grant from the National Institutes of Health.

There’s a still long way to go before decoded speech can achieve the rhythm of natural speech, but “you can see the trajectory where you might be able to get there,” said Viventi.

You might even say the technology is getting better, a little better all the time.