New implant design prevents scar tissue without drugs, MIT says

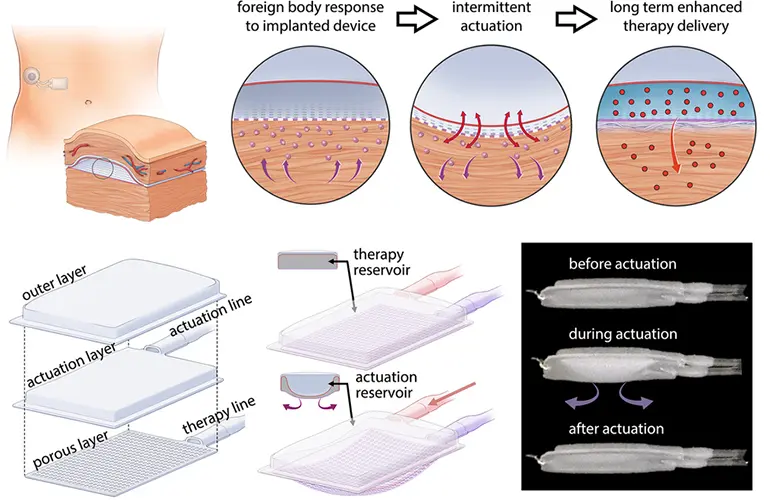

Mechanically inflating and deflating an implantable device for 10 minutes a day prevents immune cells from building the scar tissue that has been a major obstacle for artificial pancreas researchers.

That’s according to new findings from a team of MIT engineers who built mechanical deflection into a two-chambered, soft polyurethane device tested on mice. By pumping up and down for five minutes every 12 hours, the device prevented immune cells from accumulating and building scar tissue without immunosuppressants.

The researchers reported fewer neutrophils surrounding the device in the short term. And when scar tissue did eventually form, the researchers described an unusual structure of highly aligned collagen fibers instead of the tangled fibers that can lead to device failure within weeks. The aligned structure of the scar tissue that formed around the actuated devices may be easier for drug molecules to pass through.

“We’re using this type of motion to extend the lifetime and the efficacy of these implanted reservoirs that can deliver drugs like insulin, and we think this platform can be extended beyond this application,” Ellen Roche, the study’s co-senior author and an MIT School of Engineering associate professor, said in a news release.

The device could allow for the delivery of pancreatic islet cells acting as a bioartificial pancreas, immunotherapy for ovarian cancer and drugs to prevent heart failure in heart attack patients.

“You can imagine that we can apply this technology to anything that is hindered by a foreign body response or fibrous capsule, and have a long-term effect,” Roche said. “I think any sort of implantable drug delivery device could benefit.”

The researchers created a larger version of the device (120 mm by 80 mm) and successfully implanted it in the abdomen of a human cadaver using a minimally invasive surgical technique. They plan to add the ability to deliver stem-cell-derived pancreatic cells that could automatically monitor and manage glucose levels.

“The idea would be that the cells would be resident in the reservoir, and they would act as an insulin factory,” Roche said. “They would detect the levels of glucose in blood and then release insulin according to what was necessary.”

The study was published last week in Nature Communications.

Article source: Medical Design Outsourcing