Patient Engagement and Connected Medical Devices Series: Lifestyle Integration for Medical Devices

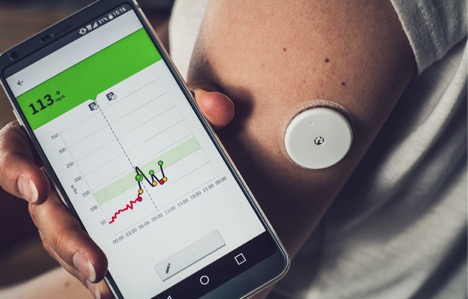

The first installment of this series was an exploration of the dimensions necessary to build a new class of devices—medical-grade lifestyle devices—that blend the best-of-breed capabilities of both medical and consumer-grade manufacturers. When combined with virtual care, the devices benefit providers, their patients, and improve the quality of care.

However, providing better-designed medical devices is only part of the industry challenge; it is also important to address the elephant in the room: Adherence. After all, even the best medical-grade sensors and therapeutic delivery mechanisms in the world are useless if the devices they are embedded in are not used consistently and properly. At the conclusion of the previous article, five device program attributes were identified that must be met to improve adherence potential, namely:

• Self-fitting

• Passive

• Effective

• Durable

• Natural

By lukszczepanski on Adobe Stock.

By lukszczepanski on Adobe Stock.

This installment of the series will further examine several user experience (UX) best practices from the consumer product industry and dive deeper into the must-haves to impel lifestyle integration for any device program.

Lifestyle Integration: From Adoption to Adherence

In the parlance of consumer products, user adoption, synonymous with product adoption, is defined as the period when patients adopt a new process or product to fill a specific need from their prior method or conveyance, because it is newer, better, faster, more comprehensive, or more efficient in some real or perceived way.

The FDA defines adherence, synonymous with drug compliance, generally as “the extent to which patients take medication as prescribed by their doctors. This involves factors such as getting prescriptions filled, remembering to take medication on time, and understanding the directions.”

The biggest barriers to adherence are the following:

• Cost. Too expensive to acquire or continue to use

• Efficacy. Does not, in actuality or perception, treat the condition

• Compatibility. Chemical or treatment protocol incompatibility or adverse effects

• Availability. Difficult to procure initially or consistently

• b>Usability. Complex instructions, usage, or protocols

When talking about the difference between drugs and devices, incompatibility—which includes potential issues such as systemic toxicity, drug incompatibility or oral formulations—is strictly the domain of the former, while all of the remaining dimensions are chief concerns of the latter. And, whereas the drug and its treatment program design are important to drive adherence, an effective medical device requires a well-designed form factor and user experience design to ensure strong adherence.

With regard to adherence, medical devices provide a key benefit that drugs, by themselves, lack: The ability to measure and proactively influence patient adherence. And with continued progress from manufacturers, both in accuracy and form factor, they can provide additional novel approaches to monitoring adherence in ways that accommodate patients by remaining inconspicuous and minimally burdensome.

Whether they be with a device or a drug (or a combination of the two), effective medical interventions for preventing, diagnosing or treating a disease require that patients adhere to the prescribed regimen.

Medical devices provide a key benefit that drugs, by themselves, lack: the ability to measure and proactively influence patient adherence.

Lifestyle integration is what happens when a product or brand seamlessly merges with a person’s life, allowing them to make it their own. These are things that people come to depend on, interact with and use regularly, coming to think of them as extensions of their own body or reinforcing their own self image. Take, for example, the noted millennial perception of brands as an extension of their own personal identities and values or the correlation between upwardly mobile aspiring owners’ self-image and their luxury SUVs.

In the context of successful medical devices, lifestyle integration and adherence are inexorably linked. One cannot exist without the other. They are interdependent. Devices that do not blend well with a patient’s manner of living will not achieve adherence, let alone experience regular use for very long.

Such was the case with Exubera, Pfizer’s failed insulin delivery bong. Among other issues, Exubera didn’t align with their target diabetic user’s desire for discretion. As was noted by commenter, Lutz Heinemann, Ph.D., in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology: In addition to being cumbersome to use—with its oversized scale and complex dosing setup procedure—patients were ultimately happier if the procedure of self-monitoring blood glucose or insulin administration did not come with the stigma of illicit drug use.

The lesson was that even if the underlying technology works fine and is also reliable in daily practice, if using the product is cumbersome, it will still fail.

In the context of successful medical devices, lifestyle integration and adherence are inexorably linked. One cannot exist without the other.

Any patient engagement strategy that aspires to achieve lifestyle integration to positively drive adherence will need to achieve user adoption to get there. How is this done? We will explore this next by examining some best practices from the consumer space.

Adoption Is Based on Trust

Let’s start with a consideration of probably the most important element of user adoption: Trust.

In building empathy for their end users, aspiring medical-grade lifestyle-device manufacturers do well to ask themselves fundamental questions such as:

• Are the claimed benefits believable? Is it presented as a panacea, or is the value proposition more concise, direct and relevant?

• Are they perceived as an honest actor? And if not, what trust-busting reputational hurdles must be overcome?

• Will users be able to easily see the value the device has in their life? How difficult is the device to learn and use, and does it perform as expected?

• Do users believe this is the right solution to help them? And if not, why?

Privacy and security are core aspects of trust. These confidence-building components are table stakes for users of any modern technology, let alone patients in a regulated care path. It does no good to pretend otherwise or assume that trust is automatically given due to brand recognition alone. Many established companies with years of history in their given market experience significant PR distress by getting this wrong. Equifax’s historic data breach, Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal, or Cedars Sinai’s celebrity health data privacy violations are all examples of transgressions such as privacy and undisclosed usage tracking, that damaged the trust between the user and company, often irreparably.

Usefulness is an important part of building trust. It’s important to consider if the overall user experience demonstrates care and consideration for the patient: If it adequately meets the patient’s needs in an effective and unobtrusive manner and if it is thoughtfully and intuitively designed—and is easy to use.

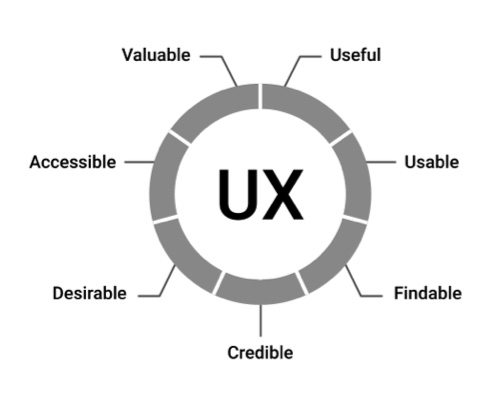

Peter Morville’s Seven Factors of UX Influence. All figures courtesy of Adrian Pittman

Peter Morville’s Seven Factors of UX Influence. All figures courtesy of Adrian Pittman

Peter Morville, a pioneer in the user experience (UX) field and author of several best-selling books on UX, cites seven factors that describe a competent user experience:

• Useful

• Usable

• Findable

• Credible

• Desirable

• Accessible

• Valuable

Usefulness is so important, in fact, that it also made Dieter Rams’s, celebrated product designer for Braun who also influenced Apple, top three of his Ten Principles of Good Design.

What is the impact when trust is not there? Skepticism. And if it goes on unresolved too long, it can have a negative impact, sending patients running for the door—”This fails to satisfy my concerns or meet my needs, so I do not trust it.” And, founded or unfounded, loss of trust in a necessary treatment or protocol can have negative consequences on public health.

Onboarding Happens Throughout the User Adoption Lifecycle

People use features, but they live with products. It is important to think holistically when designing any product. The features must be thought of as a part of a whole product. The use cases must be thought of as part of a whole narrative where the patient is allowed to discover and adopt over some period of time. This is referred to as the user adoption lifecycle. It is the progression of the user experience through a number of gradually realized and afforded user needs, occurring at key moments in time—each of which is individually defined as a use case.

To create an engaging end narrative, the product experience design must start with the first and most important use case for all products: Onboarding. Contrary to popular opinion, this is not a distinct moment in time, but rather a period occurring over multiple stages of the user adoption lifecycle. This is so important that Amazon, for example, promotes how their platform can make it much easier for smart device manufacturers to offer frictionless setup experiences to their consumers on their platform.

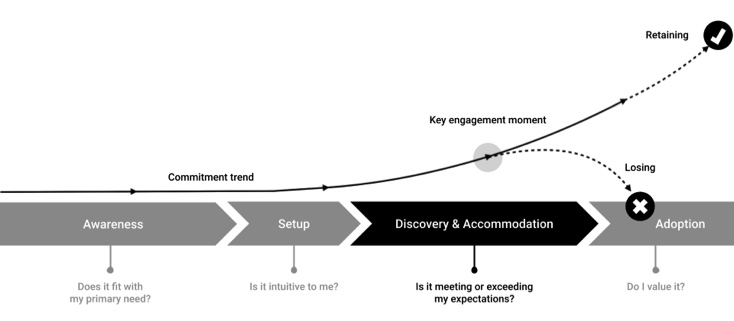

The User Adoption Life Cycle (Courtesy of Adrian Pittman)

The User Adoption Life Cycle (Courtesy of Adrian Pittman)

Awareness: For the user, this stage is fairly transactional, so simple positioning is best.

The prospective user is looking for something specific (likely a small list of critical needs). They are likely comparing multiple solutions on that front and are internalizing how strong their desire is to engage a particular solution. Simple stories are the best at this stage. Speak to the primary need and avoid overcomplicating the pitch with too many options or variables. Keep the language plain and easy-to-understand.

Setup: This should be as intuitive as possible and reinforce the primary need.

Generally, the setup stage should be as short and simple as possible. Get them using the product as quickly as possible so they can begin their discovery and accommodation, since that is where the real decision-making will take place.

The setup stage represents more than onboarding. It includes the time the user needs to install (e.g., Third party apps, plug-ins) and configure (e.g., login, download, backup-and-restore, etc.) the environment to achieve the specific goal(s) the user is focused on in the awareness stage. It’s the first stage in the user’s post-purchase rationalization.

People use features, but they live with products.

Discovery and Accommodation: This is the peak level of inquisitive interest.

The period of accommodation is the most pivotal point in the acquisition lifecycle. The user is the most “leaned in” they will be during this phase. This is where the intelligence of the product is crucial too. They are learning about the possibilities, the fit, finding out what life is like with the product (discovery). Simultaneously, the product should be honing in on the particular needs of the user and tailoring the experience to fit (accommodation).

Discovery and accommodation is a mini-cycle (length varies). Think of it like a feedback loop between user and product, the key takeaway being the product’s need to adjust to the user (accommodation) while the user explores (discovery) the product’s capabilities and fit.

Why is this important? Because in a world of semi-intelligent products and hyper-personalized experiences, the product should be accommodating the user, not the other way around. Today’s users expect the product to meet them more than halfway during the initial stages of interaction.

Catching the moment (or moments) where the decision to continue exploring, adopt or abandon is a matter of proactively identifying the leading indicators (time period, behaviors, etc.) that they are, in fact, at this stage and then proactively intervene to answer those fundamental questions (or speak to those needs) to demonstrate and/or reinforce the intrinsic value that is proposed by the product.

Adoption: The user, convinced of the product’s intrinsic value, adopts it into their routine.

At this point, the user is convinced of the product’s intrinsic value and feels the product is an extension of their values and interests. This feeling should increase over time and will be managed as a part of the retention lifecycle.

It is important to note that the cyclical action of discovery and accommodation will continue (to one degree or another) through this stage and essentially become a retention loop, where adoption becomes more about reinforcing the user’s decision to adopt or giving them new reasons to recommit (for example, with new features and personalized adjustments to the product experience over time). Making the product continue to feel new and fresh long after the initial adoption period has passed.

A successful onboarding experience concludes with a patient who is comfortable with the capabilities of the device and is more confident in using it, making it possible to attain user adoption. This is especially critical if the device intends to be “self-fit.”

Emotional Experiences Are Functional Experiences

In creating the sorts of medical device experiences that are engaging and attract user adoption, engaging patients emotionally is key. They must feel happy, satisfied, comforted, and accommodated. But achieving delight is about more than pretty visuals, friendly words, technological gimmickry, or high-minded mantras—much more.

In his book, Designing for Emotion, author Aarron Walter makes the following point about the importance of usability as the foundation of great experiences: “For a user’s needs to be met, an interface must be functional. If the user can’t complete a task, they certainly won’t spend much time with an application.”

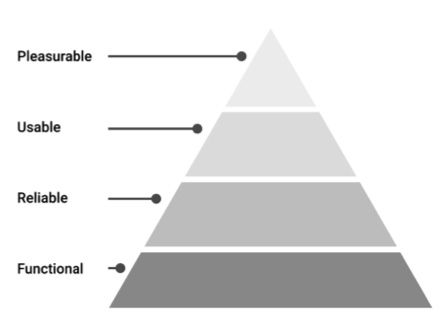

Modeled after the Hierarchy of Needs (developed by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper “A theory of Human Motivation” in Psychological Review), Walter proposes his Hierarchy of User Needs—a pyramid that places pleasure at its peak. However, it also illustrates that these are only achieved after the foundational needs of functionality, reliability, and usability are satisfied.

Aarron Walter’s Hierarchy of User Needs

How are these user needs defined?

Functional: Does it solve a real user problem? The product’s design must be purposeful. That means products that work beyond the “happy path” (best case scenarios of usage) and provide the sorts of features and capabilities that are most relevant to the need.

Reliable: Does it work consistently? For example, it should be fast and responsive when it needs to be and provide the necessary level of security for the user’s data. Product dependability is critical for successful repeat experiences.

Usable: Is it helpful? Controls must be easy to identify, comfortable to use and accessible. Information must be intelligible and in the right language. It needs to work for a wide range of user abilities and technical literacy levels.

Pleasurable: Is it enjoyable to use? That means things like clean and approachable interfaces and engaging copy. To be effectively engaging, a product needs to be polished and user-friendly. It’s not just about what you do— measuring personal EKG for Abfib, for example—but how you do it.

Achieving delight is about more than pretty visuals, friendly words, technological gimmickry, or high-minded mantras—much more.

Hospital platforms that provide patients the ability to access and use electronic health records are an example of seemingly convenient technologies that fail to engage users. A substantial amount of policy effort has been directed at this, but a recent report from Health Affairs estimates that only about 10% of patients with access actually used it. If you build it, they will not necessarily come.

Similarly, medical device designs that miss this point, miss the opportunity to engage the patient successfully and enduringly.

Achieving Lifestyle Integration Through Form Factor Diversity

In addition to all cited above, achieving full lifestyle integration also means continually exploring new form factors that provide more passive interactions, proactive interventions, and intelligent monitoring opportunities by blending ever more seamlessly with a patient’s daily activities where they live and work—expanding the definition of “wearables.”

As mentioned before, trust is key here. Otherwise, the “creepiness factor” of all those newly introduced and probing sensors will discourage any chance of adoption. But, having addressed that, the cost, convenience and effectiveness of the form factor become the next big hurdles to overcome.

If done right, it will result in a future where medical devices won’t have to look or operate like devices at all. Interacting with a blood glucose or heart monitor won’t present any more friction to use or integrate into one’s life than flipping on a light switch or turning a doorknob. Especially if passive sensors can be invisibly installed in objects patients already use every day in a similarly seamless manner.

Thinking of form factor diversity for medical devices in this way is not new. Back in 2016, researchers at the University of Buffalo explored a necklace that used a wearable acoustic sensor to monitor, recognize and recommend improvements on dietary intake by listening to and analyzing the wearer’s chewing and swallowing activity.

If done right…interacting with a blood glucose or heart monitor won’t present any more friction to use or integrate into one’s life than flipping on a light switch or turning a doorknob.

Or take the smart contact lens invented by a team at the University of Wisconsin in 2011 that autofocuses within milliseconds to enhance vision for the then estimated over 1 billion with presbyopia (farsightedness). Independent Alphabet subsidiary, Verily Life Sciences, proposed utilizing a similar format a few years later for monitoring blood glucose.

Imagining diverse solutions like these with today’s modern technology gives us things like MC10’s BioStamp. The system is a wearable health tech solution that creates comfortable, discrete sensors that can be applied anywhere on the body for targeted data collection. Their wearable sensors are durable, wireless and rechargeable and utilize a dedicated mobile application for remote data collection and guiding users through sensor application, prescribed activities and eCOA.

Or perhaps, something like the Heart Seat. Developed by a Rochester, New York–based startup focused on developing a device combines a toilet seat with a cardiovascular monitoring system. Patients can use the technology and have their heart rate, blood pressure, cardiac output, ECG and blood oxygenation checked.

Yet another example is the Jewel Patch Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillator (P-WCD), developed by Element Science, Inc. It is an unobtrusive, low-profile, wearable personal defibrillator designed to detect and treat life-threatening arrhythmias in patients with an elevated temporary risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Ultimately, modern medical-grade lifestyle devices can allow patients and healthcare professionals to remain connected. And the entire healthcare process is more efficient for professionals when these devices are paired with equally powerful cloud or on-device based PGHD (patient-generated health data) processing and analysis.

Part III: The Future of the Medical Device Industry

In the next article, we’ll conclude the series with a discussion with a select group of medical device and healthcare industry experts and pioneers about the future of patient engagement, remote care, and the potential for medical-grade lifestyle devices.

Article source: MedTech Intelligence by Adrian Pittman, Bernhard Kappe, Randy Horton