3D-printed Bioresorbable Heart Valve May Represent a ‘Paradigm Shift’

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) and Emory University have developed a 3D-printed heart valve made of a bioresorbable polymer. Most heart valve implants currently are made from animal tissue and last only 10 to 15 years before needing to be replaced. The technology developed in Georgia Tech labs, described as a “paradigm shift” by the researchers, enables regeneration of the heart valve inside the patient and eliminates revision surgery as the patient’s body changes.

Pediatric patients must undergo multiple surgeries

More than five million people are diagnosed with heart valve disease each year in the United States. If left untreated, it can have fatal consequences. Valve replacement and repair are the only methods of managing the condition, and they often require multiple surgical procedures, especially among children.

“In pediatrics, one of the biggest challenges is that kids grow, and their heart valves change size over time,” said Professor Scott Hollister, Patsy and Alan Dorris Chair in Pediatric Technology and associate chair for Translational Research. “Because of this, children must undergo multiple surgeries to repair their valves as they grow. With this new technology, the patient can potentially grow new valve tissue and not have to worry about multiple valve replacements in the future,” said Hollister in an article on the Georgia Tech website.

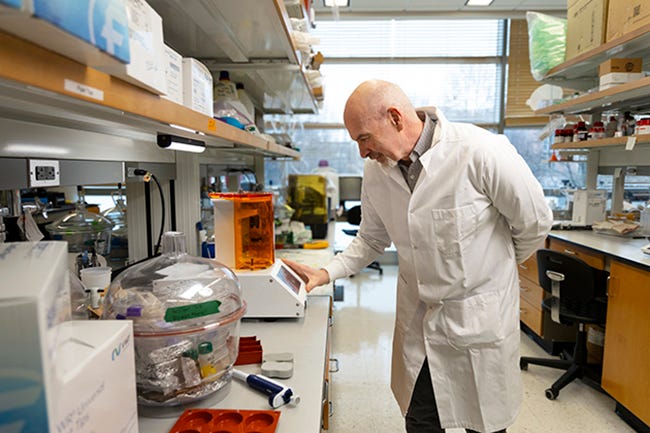

Faculty members Hollister and Lakshmi Prasad Dasi and their research teams at the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University in Atlanta led the research. Hollister is an expert in tissue engineering and 3D printing for pediatric medical devices and Dasi is a leading researcher in heart valve function and mechanics.

While 3D-printed heart valves currently exist, as do implantable bioresorbable materials, this is reportedly the first time that the two technologies have been combined to create a device with a resorbable, shape-memory material. Finding a suitable elastomer was one of the initial challenges.

Design requirements for the elastomer

Hollister outlined the design requirements for the material for PlasticsToday. The researchers had to find an “elastomer that could be tailored to match native valve leaflet properties as closely as possible,” said Hollister. In addition, it had to be able to “withstand large deformations; be resorbable in a six- to 12-month timeframe; have shape-memory properties, [such that] it can be folded into a catheter for delivery but will expand at body temperature to its final form when delivered.” The material also had to be biocompatible and support tissue growth, and accommodate 3D-printing technology, he added.

Poly(glycerol dodecanedioate), or PGD, developed in Hollister’s lab, met all of these requirements.

The unique ability of 3D printing to economically produce patient-specific implants is a key reason it was selected as the means of production. In pediatric applications, 3D printing provides specific advantages when working with bioresorbable materials, said Hollister. “The valves can be made patient-specific based on imaging data, and 3D printing [facilitates] complex structures like the leaflets connecting to the annulus for valve delivery,” Hollister told PlasticsToday. Not to mention that it is much more cost-effective for the low-volume production of custom pediatric devices, he added.

Pediatrics is only the beginning

Pediatric applications are at the heart of this research, which has the potential to fulfill a largely unmet need. Implants aren’t developed for pediatric populations as often as they are for adults because child diseases are rarer, and the manufacturing costs are elevated, according to Hollister and Dasi. Combining bioresorbable materials with 3D printing and manufacturing could be the key to developing better pediatric devices.

“The hope is that we will start with the pediatric patients who can benefit from this technology when there is no other treatment available to them,” Dasi said in the article on the Georgia Tech site. “Then we hope to show, over time, that there’s no reason why all valves shouldn’t be made this way.”

Professor Scott Hollister and his team produce the implants using a 3D printer. Image: Christopher McKenney/Georgia Tech.

That won’t happen overnight. Medtech development famously is a marathon that stretches over many years. Hollister and Dasi’s teams currently are testing the heart valve’s physical durability using computational models and benchtop studies. Dasi’s lab has a heart simulation setup that matches a real heart’s physiological conditions and can mimic the pressure and flow conditions of an individual patient’s heart. An additional machine tests the valve’s mechanical durability by putting it through millions of heart cycles in a short time.

Long path to regulatory approval

“This is a long process that will entail bench and fatigue testing, large animal studies, and finally phase I and II clinical trials,” Hollister told PlasticsToday. “From initial development to regulatory approval for a Class III device such as this will likely take at least eight years. It is possible that the device could be used in humans sooner if it were to qualify for the FDA Breakthrough Devices Program,” said Hollister, before adding that “current events affecting research funding may make this time period longer.”

Source:MD+DI